By Cate Meister

I wake up ten minutes before class starts. I use half of that time to persuade myself to get out of bed. During the other half, I put on a sweater, take a three-step walk to the table in my room and log in to my 7 a.m. zero period Zoom meeting. Even though I’m a hybrid student, I chose to stay online the week before winter break because of the rising COVID-19 cases in Orange County. With new cases at school, my entire family has been especially cautious lately. I go to school from my room because my sister and dad both attend school and work, respectively, from my house.

I usually try to keep my camera on during Zoom meetings, but it doesn’t always happen when I’m feeling tired during my zero period. When my camera is on, I feel more connected with the class, more alert and I pay more attention to the class that I’m in. I’m prone to dazing off at times, but when my camera is on, I’m more likely to listen actively and respond to what my teacher says.

However, the majority of my classmates, when given the option, don’t choose to keep their cameras on. This means I’ll spend most of the day with a series of dark boxes on my screen.

On the days that I don’t attend school physically, there is a certain disconnect between me, my in-person classmates and my teachers. The gap can stem from anything: when your audio cuts out and you can’t hear your teacher or when in-person classmates ask the teacher questions without unmuting. It’s most noticeable when in-person students don’t share their video. The teacher can see them, and in-person students can see each other, but an at-home student isn’t able to.

My zero period often entails class bonding exercises or independent work, so this usually doesn’t affect me at the beginning of the day. By the time the period is over, I take some time to organize my desk a little. One of the conveniences of being at home is that I don’t have to move any of my things between classes or even days.

My first-period class is a world language class that relies heavily on communication. We frequently use breakout rooms and the chat function to speak to each other. The class is heavily focused on videos and readings in Spanish. The more hands-on aspects of a Spanish class have come to a halt for hybrid and virtual learners alike. Instead of handwriting homework assignments in my workbook, I type them out. The conversations I have with my classmates tend to be more strained, not because they are in a different language but because it’s difficult to have a back-and-forth dialogue over Zoom.

Between classes, I try to walk around, stretch or grab a snack. The long duration of the class periods can be overwhelming. Having completed zero- and first-period classes places me only halfway through my day. The block schedule is situated so that I have four classes on Tuesdays and Thursdays and only two on Wednesdays and Fridays. The days that I have four classes tend to be more mentally and emotionally exhausting since I sit in front of the same screen for a total of around five hours, not including homework which keeps me online for longer than that.

My third-period history class also consists of a mix of independent and group work. Everything is fairly exclusively digital. I can access my textbook, primary sources and explanatory videos all through online resources. I try to take handwritten notes when I can for history since writing helps me retain information. One of the challenges I’ve found myself facing is the extra time I have to set aside if I want to print my homework or notes for my own personal learning.

By the time my third period has ended, I usually feel groggy and cramped having spent the entire day in one room. It’s easy to lose track of time during classes, so teachers, especially those that teach from home, often unwittingly hold me in class longer than expected. Sometimes this means that I don’t leave my room for the entire duration of the school day since “passing periods” are frequently cut short.

In my last period of the day, I usually work independently and then join a Zoom for the later portion of the class to review what I’ve learned in math. Unlike previous years, we don’t go over homework questions during my actual math class. The shortened schedule means that there is not enough time to review the problems from previous homework assignments. Fortunately, students who need help can attend office hours.

When the school day ends, it’s 12:32 p.m. At this point, I eat my first meal of the day, having determined that extra sleep in the morning is more valuable than breakfast.

Homework frequently takes up more of my time than the actual school day. With one Honors and three Advanced Placement (AP) classes in my course load this year, many of my teachers move at an especially quick pace to prepare me for AP exams and more advanced levels of the subject matter. Due to the digitization of classwork, I usually don’t get a break since an assignment can have an assigned due date on a day where I’m not attending that particular class. The benefits of having classes every other day are rendered pointless when homework has no limits.

Still, most students have other after school obligations. For me, this encompasses a range of activities: logging into online club meetings, attending office hours for my math class, going to work and practicing with my swim team. With the growing emphasis on the “well-rounded” student, students feel the need to precariously cram clubs, sports and volunteer work into their already loaded schedules.

The next 10 hours are something of a pattern for me: first homework, then the job that I work at, followed by more homework, dinner, homework and swim practice, ending with homework until I’ve finished it all. The amount of time I spend on homework isn’t uncommon for distance learning. I spend less time actually attending school, which means I also spend less time learning the necessary content. Shortened school days have led my teachers to push more classwork into the homework category. I hunch over my laptop into the hours of the night. I study for tests, type essays, read pages upon pages of textbooks, record myself giving a presentation, fill in digital worksheets and push aside the long term assignments for my equally homework-packed weekend.

It’s 2:00 am by the time I’m close to finishing homework. With my laptop propped open on my legs, I fall asleep.

Although there are times when hybrid learning is more convenient, school amid a pandemic is still overwhelming. At-school learning offers better connections with in-person teachers and classmates, and it’s easy for students to feel isolated at home especially when other students don’t have their cameras on. It’s difficult to find breaks from being online, and school is even more mentally draining because of it.

But I would argue that at-home learning carries one distinct advantage over in-person learning. I don’t worry about who might have sat at the desk next to mine or walking through the wrong hallway entrance. Instead, I’m able to devote myself fully to learning. I feel distinctly safe when I learn from home.

By Samson Le

6 a.m.

My alarm rings and I prepare myself for the hybrid learning portion of senior year. The drive there is as normal as it would be if there wasn’t a pandemic. Entering school, I notice that there are far fewer congregations of students as there normally are. There is no one in the bowl and there is no one in the school library. Students space themselves far away from each other, which helps to reduce the spread of COVID-19.

Additionally, staff members are sectioned off at various school blocks. They remind people to socially distance and walk according to the direction of the arrows taped on the ground. These practices are necessary to slow down the spread of the virus and maintain safety.

7:20 a.m.

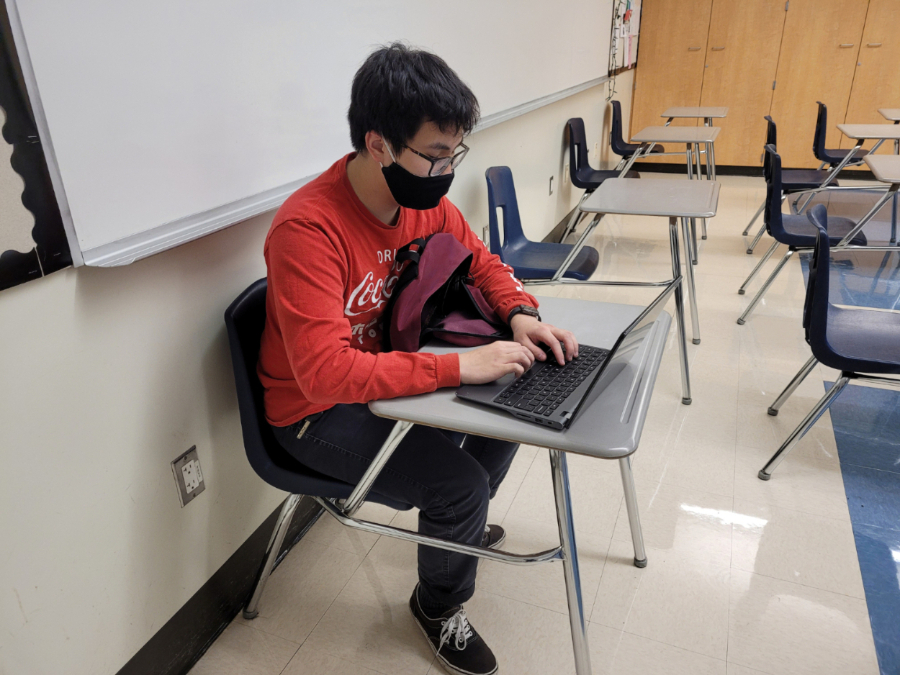

It’s time for zero period. I enter the classroom following a one way only path. There are nine students in the classroom and the rest are online. The teacher instructs me to sit in a seat that has the same colored tape used for my period. This is a very practical way to ensure that no students from different periods share the same desk and potentially spread the virus in that manner.

Class time consists of logging in to the Zoom meeting and participating in activities from there. I find that when I meet and talk to students in breakout rooms, while staring at a screen, it makes no difference to when I am just at home. I finish my work and the bell rings for first period. I exit my zero period through a different door than when I first entered to avoid the potential circulation of virus particles entering my body. The idea of entering and exiting one way is a smart practice.

8:30 a.m.

First period commences. There is joyous music playing, which energizes the room. The music is certainly a good distraction from just sitting and waiting for class to start. The protocol for my first period is different from my zero period. The teacher is protected from the students through distance and a glass shield. When it is time to interact with other students, the students who are in class face their desks toward each other to talk, while students online enter Zoom breakout rooms. The action of turning desks to talk is the most similar to normal classroom interaction. This class has done an excellent job at simulating a normal classroom environment while maintaining safety.

9:52 a.m.

The room is cold and desolate. I walk into my third-period class which has no more than three people. A substitute teacher sits at the front of the room and initiates light-hearted conversations with the students. However, the substitute serves no other purpose than just watching the students while they log in to their Zoom meetings and silently do work for the rest of class. If the point of the substitute’s job is to monitor students while they do their work, then it is better off to just be online. I don’t interact with any of the students at all, so I often debate whether it’s worth it to be here. To me, this class acts as an hour of work, which can be done at home where it is much safer there. There’s no purpose in coming to a class where you silently do work you could easily do at home while a substitute teacher chaperones the students.

11:15 a.m.

My fifth-period class is entirely online due to the course’s content being fully teachable at home, so I just go home after my third-period class.

3 p.m.

After eating my lunch, I head out to cross country practice. The way that practice is conducted now is very different from pre-quarantine. The entire team wears masks and is split up into four groups of people with about the same level of fitness. The pods must be six feet apart from each other, and they must not mix together in order to prevent the virus’ spread. When running, it is crucial that the groups start at different times to avoid the risk of being crowded together and having the virus potentially spread that way. After finishing the run, the athletes stretch in their groups and remain in their groups until they decide to go home.

5:30 p.m.

The homework load that is assigned is manageable because some of the assignments are due after the following day. There isn’t a strenuous amount of homework that is given, but the homework isn’t light work either. I have to work diligently to ensure that I can finish my work and get a healthy amount of sleep for the next school day.

Despite the hybrid learning model’s attempt to simulate a normal classroom environment, the system is bested by the online learning model. While some teachers make the most out of the new learning environment, the majority of the model consists of work periods where the teacher or substitute monitors the class. In-person instruction is not beneficial to one’s learning, and it may be better to ensure complete safety by staying in the online learning model.