By Rebecca Do

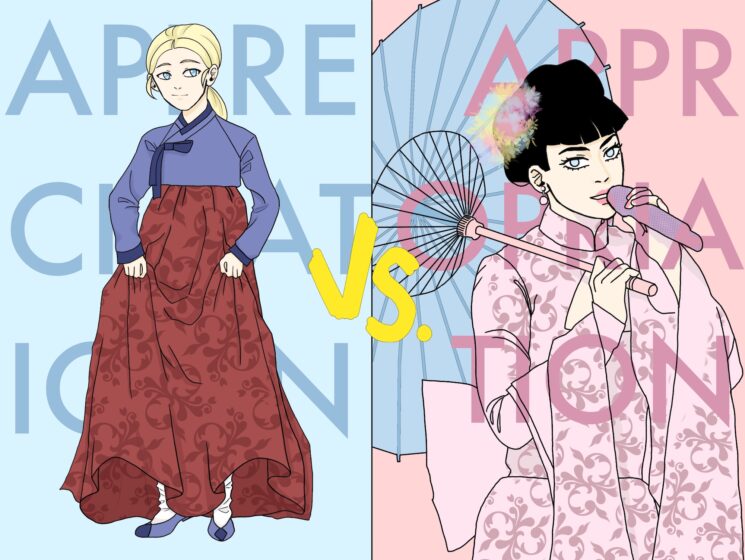

“Appreciation” and “appropriation” are syllabically similar but hold exceptionally different meanings.

One of the most recent events in which appropriation thrived was Halloween. Costume-wearing originally meant to ward off ghosts in Celtic culture has now turned into people dressing as their favorite cartoon characters or famous celebrities—this is not necessarily bad.

However, people have taken it too far when it comes to costume-wearing, turning to cultural wear when the spooky season rears its head. “My culture is not your costume” is one of the sayings popularized by the misuse of cultural wear for nonsensical purposes. This is an example of cultural appropriation.

Cultural wear and other cultural symbols hold significance to the people of said culture and the people of that heritage. You can’t adorn yourself with things that mean nothing to you but mean so much to another group of people. That is cultural appropriation—paying no regard to the culture which has influenced you for your own personal gain.

On the other hand, cultural appreciation is exactly as it sounds; it means you making an attempt to understand the culture that you’ve decided to surround yourself with.

Posing a hypothetical situation, a woman who isn’t used to East Asian food going to Seoul and being respectful of the meals she’s given is an example of cultural appreciation. After years of reading about Korea, she goes to a temple and tries on a hanbok.

Someone who I feel emulates appreciation is @blondieinchina on TikTok. She’s a white woman who has been living in Beijing for some years and doesn’t miss a beat uploading Chinese regional dishes onto her page, encouraging people to keep an open mind about new foods.

However, some people tread the line between these two often.

At the Fountain Valley High School “Fall Fest,” a club decided to sell birria tacos, traditional Mexican food to fundraise. Under one of the said club’s posts, there were a handful of students outraged at the members for making and profiting off of their culture’s food.

At first, I thought, “What’s the big deal? It’s just food.”

Then, I had to see it from my perspective. How would I, as a Vietnamese student, feel seeing a club that was majority non-Southeast Asian, selling spring rolls or pho? It would be a little odd.

Culture is important. Culture is history—it is struggle. Different people react differently to how their culture is shared, and that is what makes this conversation so difficult.

It is absolutely not in my place as an Asian person to put my two cents into something that does not affect me, so the only thing I can do is encourage people to keep an open yet critical mind.