By Priscilla Le

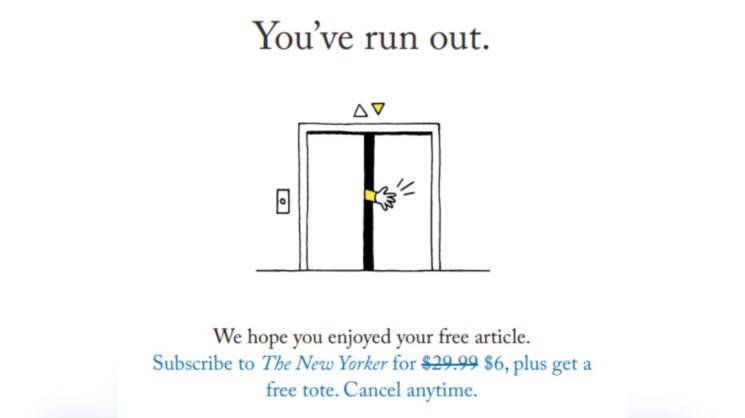

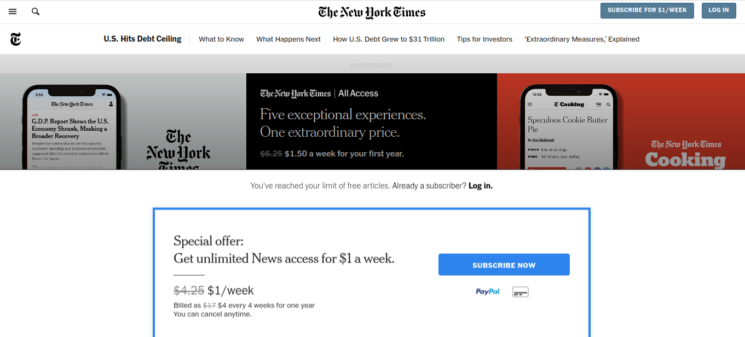

You’re a student and you’re online constantly (who isn’t in this technological age?). And since you’re a student, you have assignments that more often than not require supplementary research. So you trek your path online optimistically, typing in keywords that will hopefully point you in the right direction, looking at a few informative news articles, or attempting to. But before long—perhaps on your first link—you get the dreaded:

You shrug it off. There are more articles out there…right? Yeah, you assure yourself. You go to another link, full of hope. Blocked straight up. Okay…maybe there will be a free site somewhere else. You’re tense now, especially with that 11:59 pm deadline impending, making you regret that you procrastinated on this assignment. Another link, please work…

The screen flashes white with the all-too-familiar wording. And after many more attempts resulting in futile results, you throw your computer to the other side of the room.

We’ve experienced the traumatizing experience far too often, with endless paywalls between us and the information we need.

But how did we get here?

Well, it all started with paper newspapers. Then, the internet dawned upon us and the world was never the same. Digitized news began filling up the web and this influx of free and easily accessible information decreased physical newspaper sales as consumers stopped going out to get the paper.

Additionally, other websites started to take “a large bite out of the classified advertising revenues that traditionally supported newspapers” (Williams & Stroud), providing another blow to the papers.

Newspapers turned to online ads for revenue, but in the face of ad blockers, they were once again kicked to the curb, helpless and defenseless.

Until one solution, the glorious paywall, served to answer their concerns regarding funding not only to sustain their online domain, but also their physical papers. And although this solution did help at the beginning, now, as news continues to proliferate and our lives are surrounded by the web, internet users of all kinds have come to disdain such a practice, avoiding it like they do the Coronavirus.

So now you know. Paywalls were meant to help with the declining revenue newspapers experienced from the sudden onslaught of the technological era. So, it’s an innocent cause, right? Honestly, there is truth to that statement.

Paywalls guarantee a steady income for newspapers. And with this steady income, they are given more liberty to pay their journalists and experiment with greater security. This experimentation can lead to expansion as the newspapers are able to invest in qualified journalists and equipment to make their newspaper the most efficient, accurate, and excellent it can be.

Additionally, collecting revenue on their own provides greater creative freedom as news sites don’t have to be restricted in their article choices from sponsors. They can explore their own routes and write their own stories without having to choose between censorship or losing their newspaper from a lack of funds.

Paywalls also avoid papers from getting taken advantage of. Without some type of compensation for their work, newspapers are basically putting their work on the internet for free. That perks the ears of big tech sites, such as Google, who “get [this] content for free and then [monetize] it with ad networks” (Meehan), so that only they win in the end.

And finally, “Paywalls, to their credit, negate the need for clickbait articles to subsidize good reporting” (Meehan), which is a fancy way of saying newspapers don’t need to create flashy titles or stretch the truth to incite people to click so they get their paycheck—the paywall suffices. And that’s a good thing since quality journalism should never be replaced with erroneous or twisted “news.”

But these benefits mean nothing if no one is reading the news source.

These paywalls, which serve many benefits to the newspapers, also cause news medias to shoot themselves in the foot when their solution drives away their customers.

The first reason is that readers are less willing to pay for something they can get for free.

Back when paywalls were nonexistent, consumers were used to their online content being free. So now, the shift towards charging fees makes them relucent to pay when it previously wasn’t a requirement.

Not only that, but It is easier to click off and find another news site than acquiesce to the paywall, so that’s what they do.

Add when we consider people, most likely students, who are just going in and out to get information, the price isn’t worth it. This leaves them to leave and find another source rather than pay and stick with brand loyalty.

Not only are the newspapers harmed by a decrease in consumers, but their brand name is also associated with the disappointment of paywalls. Consumers are conditioned to click away and ultimately disregard the news media which put these blockers. And as they feel frustrated, they’ll be less likely to pay up their dolla dolla bills, instead searching for an elusive news medium that doesn’t have such obstacles to accessing the information they need.

So not only do paywalls frustrate readers, they drive them away and ultimately harm the news media as they have a decrease in viewership.

But that’s not the only tragedy. A decrease in viewership also causes newspapers to ultimately lose their purpose: to provide well-founded news to the public.

Of course, journalists should be rightly compensated for their hard work. But if no one is reading the news they are pumping out, doesn’t that serve as a disadvantage to the newspaper and the people? As humans, we educate each other. However, when there is a wall in the midst of that interaction, what can be done? These questions challenge the notion that paywalls do good. If they are cutting off our access to knowledge—if they are cutting us apart from human connection and insight—then they would do better as part of the setting of a dystopian society. But that’s just my opinion.

Laura Wilson, however, feels that paywalls are the right move in her article, “Why Putting up a Paywall Is the Right Move for Your Content.”

In it, she discusses the many ways paywalls are benefical. And although Wilson’s arguments are centered less around news sites and more around digital content in general, applying her logic specifically to news articles further highlights why paywalls don’t fit for such sites.

One of the main ideas she focuses on is the quality of the work behind the paywall. Wilson notes, “Whatever you hide behind a paywall must be worth paying for,” whether it be exclusive content only found on your website or a certain quality that elevates it above all other works on the greater wide web.

But when we apply this logic to news articles, whose facts aren’t necessarily exclusive to one source, it isn’t sound.

Sure, the work might be “better” with the writing style or whatnot, but news is more focused on the facts and less on the writing. Therefore, readers would be able to find the key facts, which are the same for every news site, from various sources and thus opt for the free version rather than buy from the paywall.

Additionally, Wilson argues that if you have a dedicated following that is willing to spend money on your content, it “can make you more attractive to advertisers and other companies looking for brand collaborations,” showing paywalls can add value to your website. Additionally, she notes, “A smaller, loyal community of customers is much more valuable than a random selection of visitors you happen to draw in each month.”

Though these assertions are correct, they are naive.

These statements come with the assumption that viewership is already attained. But what if the news media is starting fresh?

Readers coming to find answers might not be looking specifically for the specific news source, but for the story. So if the first thing they see is a paywall, it can feel alienating as they are being asked for money before they can even get to the news.

And even then, even if the price is as little as a dollar, the annoyance of a paywall can create a hostile relationship where the reader avoids the news source entirely.

Past a dedicated following, she notes that a paywall “indicates that your material is of a unique quality, and can be accessed by only those who are willing to pay for it,” implying a “small level of exclusivity.” This logic is also faulty.

When viewing a paywall, the first thing that pops up in a consumer’s head is not, “Oh, I have to pay so it’s worth it.” Instead, the thought is, “Oh, I have to pay? No way Jose.”

In the psychology of the average person, we immediately go towards the negative rather than the positive, favoring convenience rather than giving the benefit of the doubt. So in this context, exclusivity is a disadvantage, because the reader is on the outside. This causes them to be further alienated from the site.

This article also references The New York Times and how they have been successful with paywalls but fails to mention that it was already an accredited source to begin with. People are willing to pay because it is prestigious. And that’s why they can get away with it. Apply this to another news site that isn’t as well known and it’s suicide.

A disadvantage with paywalls that Wilson acknowledges is that you can’t share content, which is frustrating for readers and prevents free promotion through online sharing.

Add it to the list.

News sites are meant to provide news to the people—to be the eyes and ears of the happenings of the world and report it to the general public. But when people stop using certain news medias, as paywalls are driving them to do, such purpose is lost and the news, trapped behind a paywall, remains in a cyber prison. Eventually, it won’t require a paywall to cause people to stop reading the news altogether.

What a sad world in which people not only don’t have access to reliable news but don’t care about it.

But there are solutions to this travesty.

Not all paywalls are not created equally. There are hard paywalls and soft paywalls (Wilson). Hard paywalls completely block you the second you start reading. No articles. No free trial. No mercy.

But soft paywalls are more lenient and thus have different levels of play.

One form of the soft variety is metered paywalls. These paywalls allow a certain number of free articles before the paywall is shoved in your face, a kinder yet all the same forceful experience. But these ones can be easily avoided; if you go in incognito mode on your computer, you can bypass these soft walls, scaling them under your hooded mask (though I’m not the one to encourage you if you so choose to take advantage of this “secret”).

And are both hard and soft bad? Yes; the hard because you don’t get your information at all and the soft because you’re given false hope. But we can change that.

Short-term solutions include first transitioning hard paywalls into their soft counterparts and from there making the soft paywalls more lenient. This can be done by extending the maximum amount of free articles or providing free deals to certain groups (e.g. students, perhaps).

This would allow students or the general public to access information quickly and efficiently, paying off in the long run. Maybe it won’t end up in a membership, but that information can be used to educate the public, be used in club meetings where students are being educated together and spread information about current events that need to be shared. The impact need not be financial, it can be educational, relational, and communal. All from unrestricted access to the news.

Additionally, allowing access to students can educate our youth, allowing them to actively participate and know what is happening in the world. We know that these people are our future. Why not give them a leg up and foster this growth now?

But these solutions, although helpful in the short run, aren’t sustainable. Providing free memberships or articles comes at a cost to the newspaper. Therefore, investing in long-term solutions is crucial.

Long-term solutions include implementing multiple sources of income. Tipser notes, “Like in natural ecosystems, more diversity means dependencies are minimized which leaves the entire system in a healthier state.” Some examples include E-commerce such as merchandise or specialized ads. With greater income diversity comes limited dependencies on one source over another.

This means that newspapers can actually implement the short-term solutions into their long-term plan. As they are diversifying their income, they can put less emphasis on paywalls and allow such leniency that begets tremendous benefits. All this without compromising the financial health of their newspaper.

Newspapers reserve the right to decide how to collect funds however they see fit without a seventeen-year-old hating on them. But that is especially why my viewpoint is so important, being a consistent user of their mediums.

I can’t afford nor desire to spend obscene amounts of money and time buying subscriptions or finding their alternatives, nor do many of my classmates.

They aren’t just annoying for the viewers, they are detrimental to the paper. So, lift the paywalls.