By Stephanie Nguyen

I was so whitewashed. It’s a harsh truth, but it had to be acknowledged.

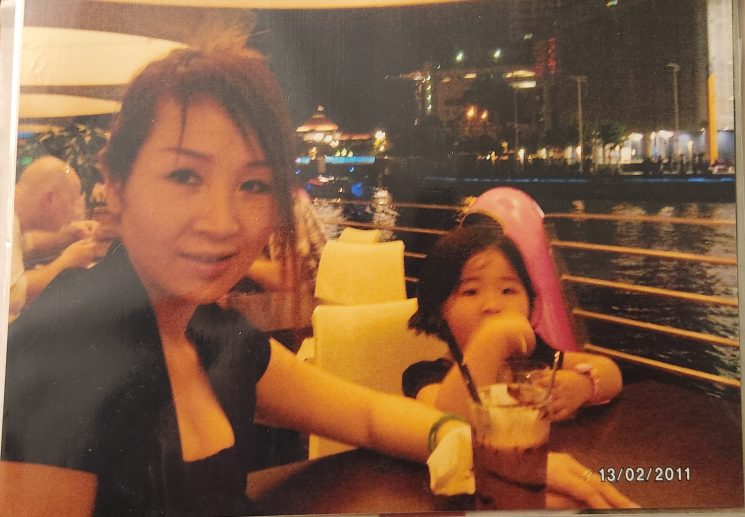

When I came to America from Vietnam on a sunny June morning in 2015, my new environment captivated six-year-old me. Never had I seen anyone with blonde hair, an afro, or a strong Greek nose. Then I saw my mom–who I hadn’t seen in two years–standing at the airport, her face completely foreign to me. I had no memory of her before this event.

It wasn’t until I was around seven to nine years old that I wanted to assimilate into American society. Not only did I want to eat hamburgers, tomato soup and cheese (see how limited my knowledge of American food was at the time?), but I couldn’t care less for the fried rice my mom made, Lunar New Year (unless I got money) or ao dais. My mom wouldn’t encourage me to participate in my own culture; she rarely spoke to me because she was so busy.

It didn’t take long for me to forget my native language because I spoke English whenever I could. I only spoke Vietnamese when I stepped off the airplane, now I struggle to read at the first-grade level.

Seven years later, I procrastinated again. Instead of doing work, I was replaying forgotten memories preserved like old relics, taking them out of their dusty homes in the cluttered attic (aka my brain). Then I remembered a cool picture book I read in Vietnam, called “The Peacock Princess.”

The fun illustrations told the story of a princess from the Peacock Kingdom, who fell in love with a prince from a distant kingdom. She went to his palace while he went off to fight in a war, but a witch framed her by telling the king she started the fighting his son was involved in. Yet not only was she wrongly accused, her advice helped her lover win over his enemies. However, the king believed her, so ordered the princess’s death. Fortunately, she escaped, and she was brought back after the king realized his mistake.

Although this folktale was of Indian origin, it made me remember other tales like “Tam and Cam (Tuhm and Kahm),” which my grandmother told me one night. It’s similar to Cinderella until the stepmother kills the main character. Years before that, I watched a YouTube video narrating “The Raven and the Star Fruit,” a tale meant to teach a lesson about greed.

After re-reading these tales, I tried to find sources documenting how they came about, but nothing came up. Then I found a legend called “Lạc Long Quân and Âu Cơ.” The titular characters were mythical entities from whom all Vietnamese were from; one of them was a dragon and the other an immortal lady, respectively. The second I finished reading about it, I did more research about the origins of the Vietnamese people, falling down the rabbit hole from fiction to fact.

Historically, they lived as tribes around the Red River Delta. A series of struggles for power ended when the Chinese took control of the country in 111 BC until about 939 AD by the Han Dynasty. For about a thousand years, the Chinese ruled over Vietnam, the latter paying tribute.

They tried to force the Vietnamese to assimilate by making the locals wear Chinese clothing, speak Chinese, learn Chinese philosophies, etc. I learned the Vietnamese tried to subvert their foreign overlords whenever they could. For example, they wrote in Chinese but spoke in Vietnamese with each other.

Centuries later, the French colonized Vietnam and called it Indochina. Rather than Westernize themselves to forget their heritage, the Vietnamese took inspiration from foreign influences, put a Vietnamese spin on it and made it their own. The proof of this is the invention of the Vietnamese banh mi. Bánh mì sandwiches are baguettes stuffed with meats, cilantro, pickled vegetables and pate with variations existing both at home and abroad in restaurants in areas such as California. The baguette and pate are French, while Vietnamese meats such as Chả lụa (Vietnamese meatloaf), heo quay (pork belly), etc. give the sandwich its unique blend of flavors. The Vietnamese take pride in who they are as a people, but they adapt whenever they need to.

Looking back, I should’ve had the same view about my Vietnamese identity. It was necessary for me to adjust to my new country, but I erased parts of myself to make room for those changes. Instead of adapting, I felt like I had to pick between being American or Vietnamese. Even as I’m writing this, I couldn’t believe that I–an immigrant– was like this at a really young age (about seven to nine years old, see the second paragraph). I’m not a hundred percent sure why I wanted to assimilate in the first place.

Nonetheless, I’m quite glad I had my little adventure on the internet. As recently as three years ago, I slowly began regaining interest in my culture, but it wasn’t until the folktales and this article that I reflected on what happened and tried to find out why. It was a pervasive feeling that I couldn’t place for years.

Someday, I’ll visit Saigon again. I recently saw photos from someone still living there; it’s gotten much bigger and more metropolitan. I guess a lot has changed in a decade. If I ever return, it would be way after I graduate high school. By the time I’m done with college, I won’t have seen Saigon in almost two decades.

Oh well, I’ll remember. It’s now number one on my bucket list.